Some of the lab members enjoying a walk under a waterfall in the reserve.

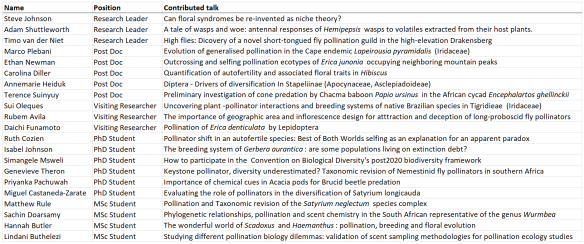

Research days have proven to be an excellent forum for lab members to report what we’re are up to, to discuss our ongoing work and exchange ideas for what’s next. From the 17th to the 20th of February 2019, the lab stayed in the research accommodation at Kamberg Nature Reserve in order to do just that. The days involved talks from every lab member who could join as well as exploring the beautiful nature reserve around us. It was also a great opportunity to get to know our fellow lab members – the new and the mainstays.

The joy of eating good food with good people after a day of good talks…

Working as part of a lab is important because of the interaction that is made possible by the experience. Science can be a lonely career. For those of us who are field biologists; it includes many days working away, often in what feels like the middle of nowhere. There is pressure to come up with a new idea, whilst worrying whether someone else has done it already. Then there are the days of intense lab work; gazing into a microscope or waiting for hours as you run a gel. And finally, there are the days of sitting alone at a computer writing it up and criticizing every sentence. Throughout this process, there may be moments when you doubt your ideas or your methods and whether your research is relevant or interesting.

Sharing the gift of interesting research with fellow lab members.

But science doesn’t have to be like that! As it turns out, you don’t have to do everything yourself. And that project you were getting stuck on and losing interest in? A colleague may be able to provide you with feedback so that it makes sense again and the excitement returns. Other people can bring in a new insight that can be refreshing and ignite something new. Collaboration often results in great discoveries and a better outcome with more thought going into the project. Listening to people give talks about their research for a whole day may be exhausting, but never did it get boring. It is reassuring to know how other people are doing and to know that you are in the right place with the right people. This is where your research belongs.

A long hike meant we could get up close and personal to the Game Pass Shelter, which has some of the best San art recorded.

These research days were held in a pristine nature reserve that fell in the Maloti-Drakensberg Park World Heritage Site. With stunning mountains, plant and wild life, we enjoyed our usual activities; this time with the company of others enjoying it with us – looking for orchids; stopping to watch jackals; spending hours attempting to photograph a plant-pollinator interaction; swimming; and hiking. And perhaps unusually for many of us – getting to see some of the best examples of San art! With the help of a guide, we did the long walk up the mountain and peered at the stone, listening to how much meaning these ancient drawings held.

Perhaps the San people who had originally applied a paint-like applicant to the stone would not think of themselves this way, but scientists perhaps they were. Every image is an explanation for how they thought the world worked; every animal showing exquisite detail required when determining the world around. And who could not be a scientist when standing on the top of a Drakensberg mountain? As scientists, our lab members attempt to make sense of the world around us too. And every time we go out, there are more questions to be found and more research to be done and always more talking about it.

Text: Hannah Butler.

Photos: Miguel Castañeda Zárate; Carolina Diller.