Our publications page has recently been updated! Whilst 2020 and 2021 was a strange year for all of us field biologists, it meant that many scientists holed up and spent the time in lockdown to write. Here are just five abstracts and cool pictures from our 2021 publications.

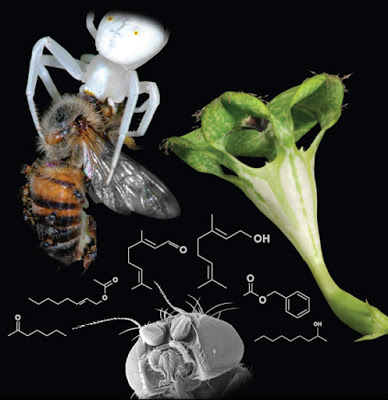

Sexual deception of a beetle pollinator through floral mimicry. Sexual mimicry is a complex multimodal strategy used by some plants to lure insects to flowers for pollination. It is notable for being highly species-specific and is typically mediated by volatiles belonging to a restricted set of chemical compound classes. Well-documented cases involve exploitation of bees and wasps (Hymenoptera) and flies (Diptera). Although beetles (Coleoptera) are the largest insect order and are well known as pollinators of both early and modern plants, it has been unclear whether they are sexually deceived by plants during flower visits. Here we report the discovery of an unambiguous case of sexual deception of a beetle: male longhorn beetles (Chorothyse hessei, Cerambycidae) pollinate the elaborate insectiform flowers of a rare southern African orchid (Disa forficaria), while exhibiting copulatory behavior including biting the antennae-like petals, curving the abdomen into the hairy lip cleft, and ejaculating sperm. The beetles are strongly attracted by (16S,9Z)-16-ethyl hexadec-9-enolide, a novel macrolide that we isolated from the floral scent. Structure-activity studies confirmed that chirality and other aspects of the structural geometry of the macrolide are critical for the attraction of the male beetles. These results demonstrate a new biological function for plant macrolides and confirm that beetles can be exploited through sexual deception to serve as pollinators.

The functional ecology of bat pollination in the African sausage tree Kigelia africana (Bignoniaceae). Plants often interact with a wide range of animal floral visitors that can vary in their pollination effectiveness. Flowers of the African sausage tree Kigelia africana are visited by bats and bush babies during the night and by birds during the day. We studied

floral traits (phenophases, scent, color, and nectar chemistry) and the visitation frequency and pollination effectiveness of different flower visitors to determine whether K. africana is functionally specialized for bat pollination. We found that flower opening corresponds with bat activity, flowers emit scent dominated by aliphatic esters and alcohols, and that nectar is produced in copious amounts accessible to bats. Pollen deposition on stigmas was twenty-fold greater per visit by bats than it was per visit by birds, likely a result of the close morphological fit between snouts of bats and the flowers. However, bat visits appear to be rare at some sites and the delayed senescence of flowers that are open throughout the morning provides an opportunity for additional pollination by birds. We conclude that K. africana is primarily adapted for bat pollination, but is also able to exploit other animals for pollination.

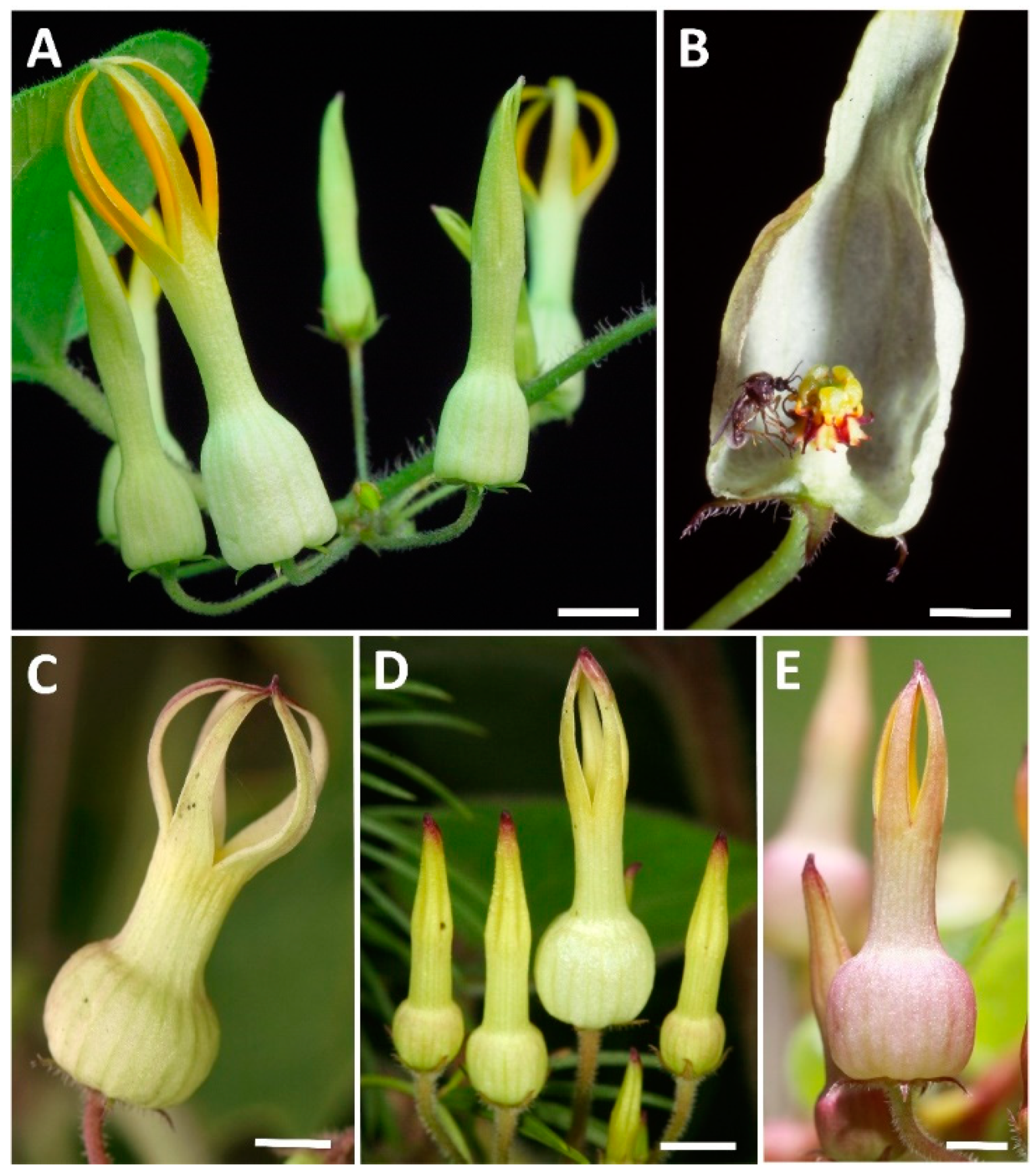

Fly Pollination of Kettle Trap Flowers of Riocreuxia torulosa (Ceropegieae-Anisotominae): A Generalized System of Floral Deception. Elaborated kettle trap flowers to temporarily detain pollinators evolved independently in several angiosperm lineages. Intensive research on species of Aristolochia and Ceropegia recently illuminated how these specialized trap flowers attract particular pollinators through chemical deception. Morphologically similar trap flowers evolved in Riocreuxia; however, no data about floral rewards, pollinators, and chemical ecology were available for this plant group. Here we provide data on pollination ecology and floral chemistry of R. torulosa. Specifically, we determined flower visitors and pollinators, assessed pollen transfer efficiency, and analysed floral scent chemistry. R. torulosa flowers are myiophilous and predominantly pollinated by Nematocera. Pollinating Diptera included, in order of decreasing abundance, male and female Sciaridae, Ceratopogonidae, Scatopsidae, Chloropidae, and Phoridae. Approximately 16% of pollen removed from flowers was successfully exported to conspecific stigmas. The flowers emitted mainly ubiquitous terpenoids, most abundantly linalool, furanoid (Z)-linalool oxide, and (E)-β-ocimene—compounds typical of rewarding flowers and fruits. R. torulosa can be considered to use generalized food (and possibly also brood-site) deception to lure small nematocerous Diptera into their flowers. These results suggest that R. torulosa has a less specific pollination system than previously reported for other kettle trap flowers but is nevertheless specialized at the level of Diptera suborder Nematocera.

A shift in long-proboscid fly pollinators and floral tube length among populations of Erica junonia (Ericaceae). Macroevolutionary studies frequently emphasize the importance of pollinator shifts for driving speciation within the angiosperms. Pollinators have been identified as a driver of diversification in the mega-diverse genus Erica in the Cape Floristic Region of South Africa, but basic information on pollinator-driven divergence at the initial stages of speciation in this genus is lacking. We focus on two populations of Erica junonia (var. junonia and var. minor) that occur on adjacent mountain ranges separated by c. 10 km and which differ in floral tube length, and ask whether these differences in tube length are associated with a shift between pollinators with different proboscis lengths. In addition, we assess whether the two forms differ in their ability to reproduce in the absence of pollinators. Our findings show that different Erica junonia varieties are visited by different nemestrinid fly species in the genus Moegistorhynchus, and that their floral tube lengths correspond to the proboscis lengths of these flies. Pollinator exclusion experiments show that the short-tubed var. minor is capable of producing seeds in the absence of pollinators, whereas the long-tubed var. junonia depends fully on pollinators. Our study provides an example of pollinator-driven divergence on a small spatial scale and contributes to an understanding of diversification of the genus Erica.

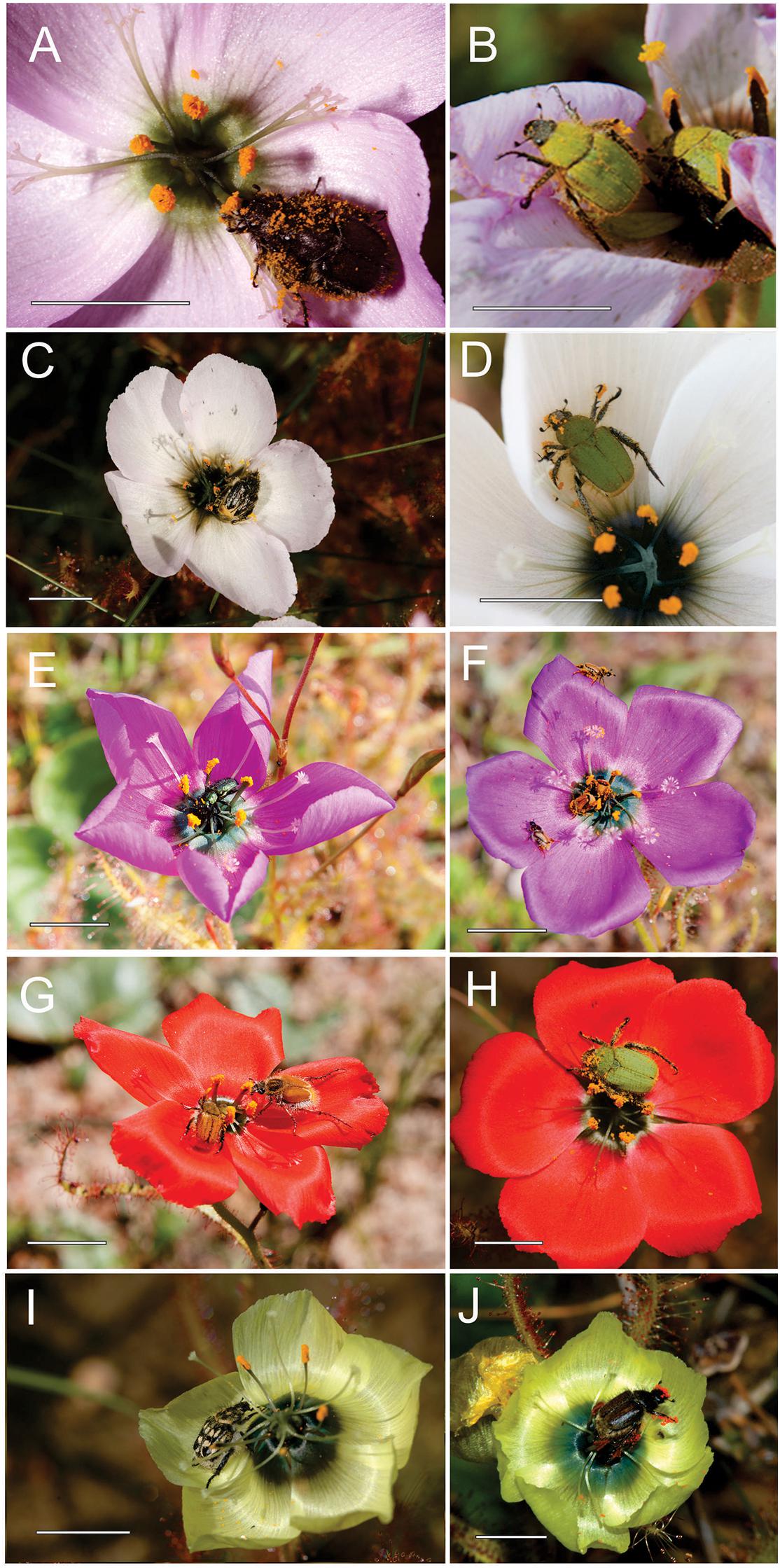

Pollinator Community Predicts Trait Matching between Oil-Producing Flowers and a Guild of Oil-Collecting Bees. The impact of pollinator community diversity on trait matching in plant-pollinator interactions is poorly studied, even though many mutualisms involve multiple interaction partners. We studied 10 communities in which one to three species of oil-collecting Rediviva bees pollinate the long-spurred, oil-producing flowers of Diascia “floribunda” to examine how pollinator diversity affects covariation of functional traits across sites and trait matching within sites. Floral spur length was significantly correlated with weighted grand mean foreleg length of the local bee community but not with foreleg length of individual bee species. The closeness of trait matching varied among populations and was inversely related to pollinator community diversity. For all bee species, trait matching was closest at sites characterized by exclusive pairwise interactions. Reduced trait matching associated with increased community diversity for individual pollinator species but close matching at the community level supports the importance of community context for shaping interacting traits of flowers and pollinators.